ODRADEK! is the fortnightly newsletter of The Odd Review, publishing short-form pieces, fragments, and serialisations—both in print and online.

Subscribe to receive each new issue in your postbox every two weeks, or buy this edition as a one-off here:

Hello odradeks,

A few things have changed since our last issue. We’ve decided to limit the length to two pages so that it’s more digestible and more manageable to produce. In addition, we’ve launched a physical print version of the newsletter.

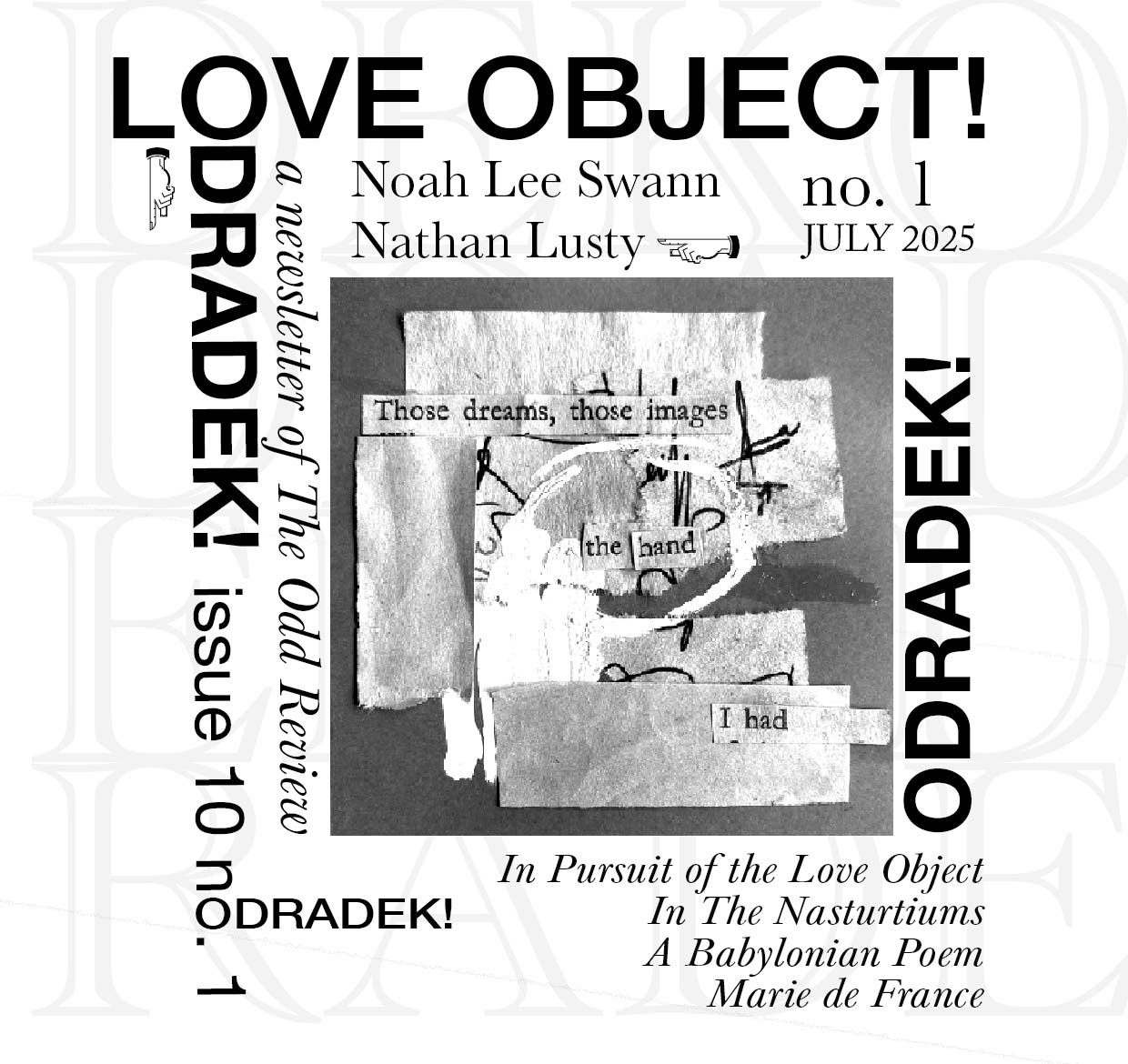

ODRADEK! is now a fortnightly newsletter of The Odd Review. Each issue explores a theme across a short series of dispatches published both online and in a limited print run of 50 collage-style newsletters. The idea is to keep printing costs affordable and allow the object itself to become an artwork in it’s own right: much like the Dada or Fluxus publications.

Issue 10: Love Object! will unfold over four instalments (No. 1–4), released every two weeks. This is the first. In August, we’ll begin Issue 11 with a new theme.

You can order Love Object! (No.1) here on Ko-Fi. Or, if you are in London you can pick a copy up from Abney Books in Stoke Newington. Message us with any enquiries.

Enjoy!

NLS

In Thomas Hardy’s In Pursuit of the Well-Beloved, the sculptor Jocelyn Pierston, seeks to create in his work an image of the 'Well-Beloved', an idealised form of feminine beauty. For Jocelyn this ideal is found fragmented in the various women he falls in love with. The sculptor flits haphazardly between romantic attachments, from woman to woman, chasing this mirage for his whole life. Despite his efforts to possess The Well-Beloved, it eludes him, appearing again in a glimpse of a new object of desire.

This provides us with a definition of the love object in classical Freudian psychoanalytic terms. The love object is whichever woman the Well-Beloved has appeared in for Jocelyn: it is the person who is loved by the individual’s ego. The love object is substitutive, trapped in an oedipal system, shaped by early relational patterns and always, in this sense, idealised.

The Well-Beloved is more real than any of the actual women Jocelyn pursues. The women he declares his love for are in fact dispensable and substitutive of this more real image. In fact, The Well-Beloved is the constant value that structures Jocelyn’s desire, and reduces any encounter with the other to a subordinate reality: the dream replaces his reality and the material world becomes a mere reproduction. For Jocelyn the love object is a mere receptacle, into which he is pours his self-made ideal. When the sculptor’s ideal fantasy clashes with the real, the ego’s fantasy doesn’t give way only the receptacle—the substitutive love object. It’s this dissatisfaction that necessitates a loop back to a searching for the Well-Beloved.

“At the height of being in love,” Freud writes in Civilisation and its Discontents, “the boundary between ego and object threatens to melt away.” It’s clear that Jocelyn never experiences this radical threat presented by the love object. The narcissism and almost autosexual egoism of this fantasy is palpable. Jocelyn’s ego seems to be immune to the traumatic effects of love, immune to this ‘threat’ to the ego. This object that Freud refers to in this passage seems to be at odds with Jocelyn’s tepid love objects. And if there is no height of being in love, if there is no excess, if it is subordinated perpetually to the ego, then surely there is no love. Love is an intensity directed at its object, in itself it is defined by this excess.

If love at its highest point is this radical threat to the boundary of the ego, its object must be more than a vessel for a fantasy or it is nothing at all. It must have a revolutionary potential to reconfigure the amorous subject’s relationship with the real. Not because the love object is an ideal, but because in the encounter with the real object that this ideal veils, the ego is confronted with the gap between itself and the other. And, more astonishing than this realisation of the gap, is the extraordinary reserves the ego exhibits in its attempt to bridge it. Despite the threat the love object poses to the ego’s integrity, in a state of love, the ego tries, still, to reach the other. This project, which will take place over four publications, is in pursuit of this revolutionary Love Object.

You always had a rather childlike manner

of drawing with a colour pencil. This

is what you told me as I sat for you.

And after you had scrutinised me

for several minutes, you showed

me a rather esoteric looking face: a web

of lines for hair, a strange instrument

for a nose. ‘That,’ you admitted

a little sheepishly, ‘that’s you!’

You write, you say, because

it's immediate. It creates a world;

it doesn’t mimic one: You write the word ‘tide’,

you write the word ‘clock’, you write ‘Wales’,

and immediately these things arrive

in some form, at least. There’s no need

to draw every black pebble on the beach,

every shimmer of every wave. Afterall,

how would you draw the brittle chalk sound

they make under foot? The pebbles, I mean.

How would you draw the wind in our ears.

That was your point, I guess – why wait?

why not walk out into the garden with a glass of beer

and walk the dogs on a summer evening,

telling me over the phone about the future

you’d dreamt for us. Why not

build around you those sad castles,

towers, walls and monasteries

that only you can see, that only you can move

in and out of, effortlessly; why not look on at the collapsed walls

the battlements and ivy covered

stones, and say, smiling, that it’s lovely

because it is no longer you.

And walking along like this

with you by my side, the black pebbles

underfoot, I begin to think you’re right:

There is more wind to the wind, more

grey-green to the grey ocean, more

so much more than enough detail, like the millions of wild flowers I know you love,

which look up at you, expectantly,

for your sea-green, cow-heavy eyes to grace them

with attention. It’s enough, if you feel it,

to make you nauseous, break out into a cold

wet field of those round green wheels –

the nasturtium leaves – each with a single silver bead of dew

right at its centre, which you feel, is hiding something

from you, like that time you walked into a whispering classroom and everyone fell

silent and then laughed.

And you wished then as you do now that you could suck

the globe of dew from the hilt of a nasturtium leaf,

turn purple, swell up big as a balloon and float away.

Or even just to arrange your head

among the liquorice scented leaves

so their round, green wheels are above you

like cocktail umbrellas and you are the cocktail.

And then you’d stare up at the sky.

That, you said, that would be OK, too.

You are kneeling on the floor, writing in a little book.

You are Marie de France! And I am drawing you,

with a plait over one shoulder. You almost glow

when you are concentrating and suddenly I don’t care

for how anything should behave, least of all you or this drawing. I prefer our

playfulness,

your mannerisms, our jokes. A world in italics, a nickname for it all

even for the small distance you give me, which one day will be big

but for now is barely discernible, like a web or a breath

or a cool mist concealed in the way you blink your eyes, how they close for just too

long.

The drawing removes me like this, to a place apart from you

and in this way perhaps it was preparing me this whole time. Because,

I must just lose whatever picture of you I had, I know,

allow myself to float above you as a hand holding a pen floats above a page,

like a small moon.

END.

The odd review ALWAYS delivers