REVIEW: Anna Weyant at Gagosian

Odette Fangstrem reviews Anna Weyant's 'Who's Afraid of The Big Bad Wolves,' at Gagosian, Davies Street in London.

by Odette Fangstrem

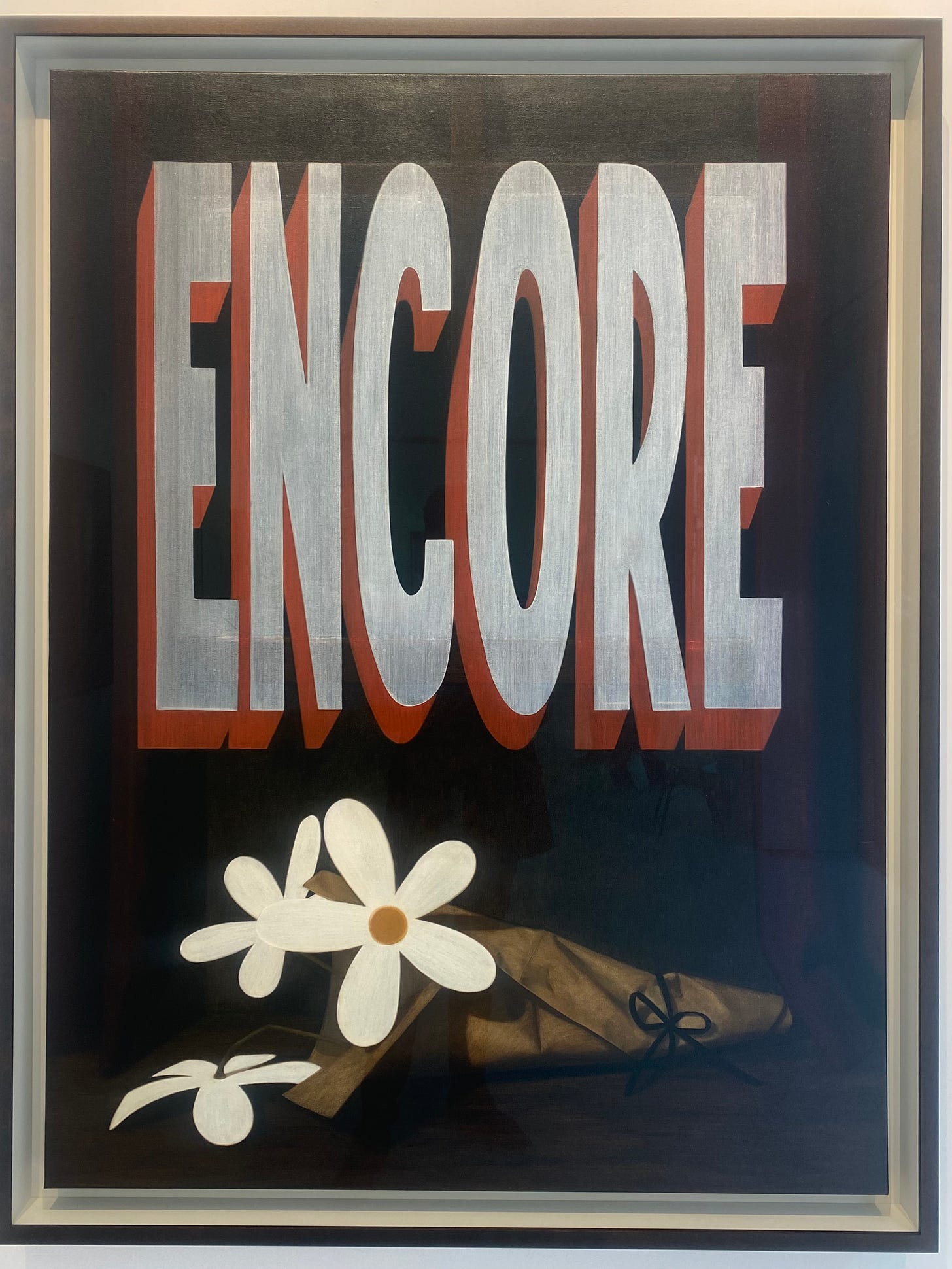

Towards the end of last year I wrote a short review of Anna Weyant’s first London exhibition at the Davies Street Gagosian gallery and posted it as a fragmentary piece on my Instagram. The show was relatively small, consisting of little more than half a dozen works under the name Who’s Afraid of The Big Bad Wolves. Since then I have learnt a little more about Weyant and the sexist mistreatment she has received by the media and the gossiping art world. On one hand Weyant is as private as most artists, on the other hand she is a celebrity, and seems not only comfortable in that elite, silicone world but to be inspired by it. In fact, one could make an argument that it has become the subject of her work, in a sense comparable to Andy Warhol. Speaking about vintage Playboy Weyant told GQ magazine: “I love the big, blond hair, and the giant, really bulby tits.”

Owing to her privacy, I know very little about Weyant. She was described by GQ as “tiny, with a bright blond bob and a high, sweet voice,” her friend, the podcaster Eileen Kelly said, “She’s like a little doll. I just want to put her in my pocket sometimes.” And yet this saccharine description doesn’t seem to add up to her remarks about Playboy.

There are further contradictions, she is from New York, she comes from a family of lawyers and she began painting at a school camp when she was about 14 years old, which she speaks about as though she had picked up knitting. Still in her 20s she became the youngest artist represented by Gagosian. A short while later she had a brief relationship with Larry Gagosian, who was 50 years her senior. The controversial affair was a storm in a teacup for the art world, and became the subject of a lot of gossip and bad behaviour by the media.

When asked if she could understand why people were so interested, she said very quickly: “Oh, totally, I would be fascinated.” And yet, in the same interview, one can’t help but get the sense that this softly spoken, slightly hesitant woman values her privacy and has been hurt and angered by the dogged obsession with the story.

There seems, however, to be very little online about Weyant’s work and her artistic concerns. This piece is an attempt to move the conversation away from rumour mongering and engage more critically by extending the ideas of my initial, fragmentary review of the young painter’s debut in London.

The first painting in the gallery, called Unboxing (2024), shows a cartoon woman, aloof, jaded, surrounded by gifts wrapped up and tied with ribbons. The woman holds one end of a ribbon but, eyes closed with ennui, head heavy in her folded arms, she lacks the energy or excitement to actually pull the wrapping open.

The only thing that troubles this painting is the small inclusion of the ribbon’s jaunty shadow, which provides a third dimension to the otherwise cartoon scene. The shadow lies in a gentle curve along the front of the gift almost perpendicular to the small band of ribbon that the woman pulls. It’s the naturalism of the ribbon that becomes accentuated by the shadow. Its möbius fold, its ‘realism’, in a sense, arrives. And this causes a small disjunction of meaning: if this isn’t a cartoon, then what kind of reality is this? It's as though we have been removed to a second frame that reveals a painting within a painting. It’s this shadow of a ribbon that suggests a reality folded somewhere within the superficial world of the cartoon.

This is Weyant’s genius: in every painting there is an equivalent to this ‘shadow of a ribbon’, some simple detail that alters, not the painting, but our perspective of the painting and its subject. These small revelations usually take the form of a small ‘crack’ in logic, provided by a shadow, a shift of perspective, or concept, a nail in a wall, a strand of hair, or a fig leaf left half-painted .

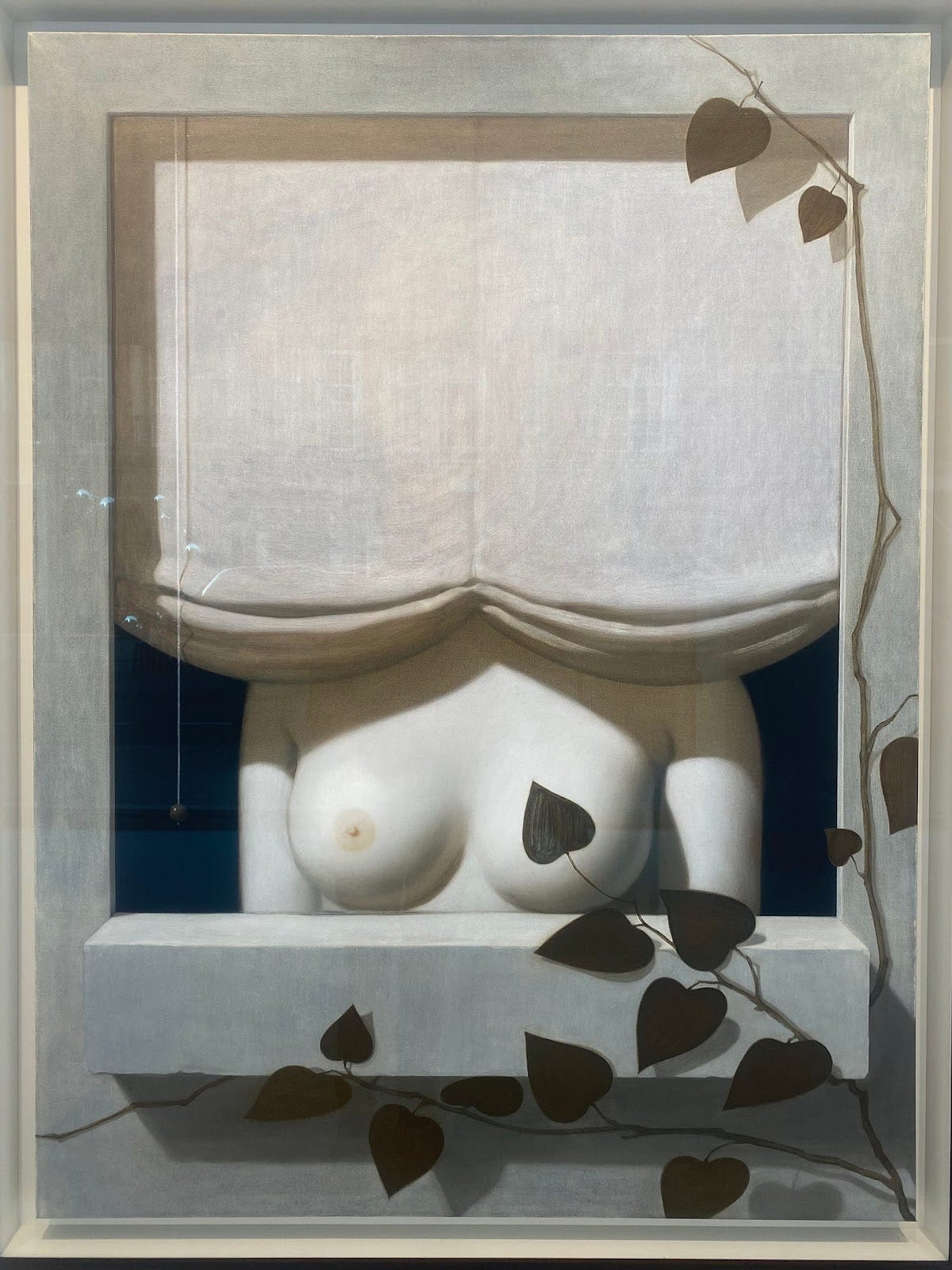

All that is visible of the girl in Girl At The Window (2024) are the porcelain-white, perfectly round and unrealistic breasts, and her upper arms. Her head and shoulders are obscured by the beige canvas blinds.

There is a precision to the painting that, like Magritte, is used to give a staid, emotionally stinted feeling. But, where Magritte’s stylisation was towards a blandness - almost dull in its committed aversion to beauty - Weyant’s is a kind of mannerism. She exaggerates and perfects features. The result is not blandness, but a frigid chill: The environments depicted are always domestic, but are shorn of any character or personality, they are like Sims houses. Similarly the figures, the women Weyant paints are exhibited, without a sag or wrinkle or blemish or body hair.

I told my partner that I found the paintings tense, performed and quietly disturbing, but couldn’t articulate much more than this at the time. He didn’t find them disturbing at all. But, it’s this suffocating perfection that provides the tension. Its like watching a tightrope walker who we know has been on a bender the night before. We know that it’s unsustainable and the smallest breath of wind could ruin the entire facade. What Anna Weyant does, is give us this destabilising element.

What subverts Girl At The Window is the hessian, sagging heft of the blinds, almost fleshy in comparison to the marbled perfection of the girl. There is always one small but erratic detail that seems to disturb the otherwise complacent tranquility of Weyant’s images. A schizo detail, an unhinged thing that just by its inclusion, very subtly suggests the delusion is the norm; it is the schizo detail — the ‘shadow of the ribbon’, the ugly blinds — that is real.

There is obviously a homage being paid to Magritte in this Gagosian show. As a painter, Magritte had a similar genius for these subtle shifts of meaning in the forms of jokes and stiff absurdities. But in Weyant’s hands this sensibility feels like something of a lament. There is a tremendous sense of absence, a disquieting stillness. Some ordeal or self or emotion that has not ‘yet’ entered the frame, that has been repressed, rather than a self that has been abnegated.

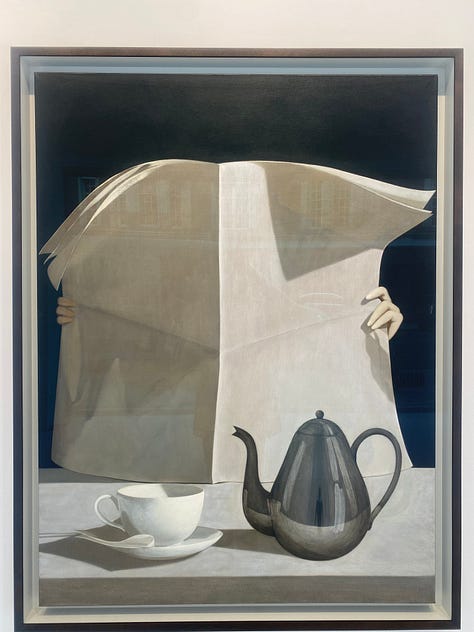

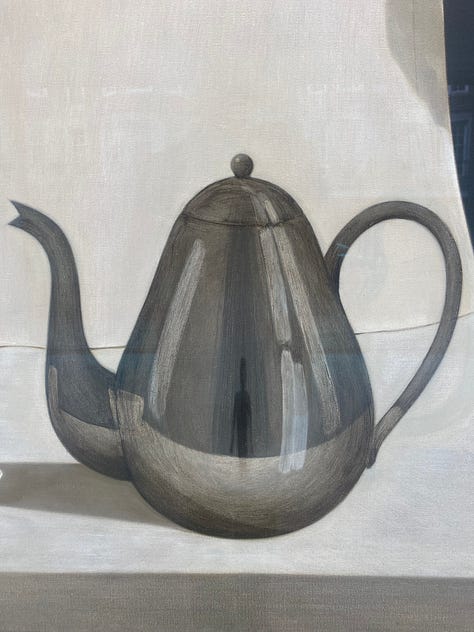

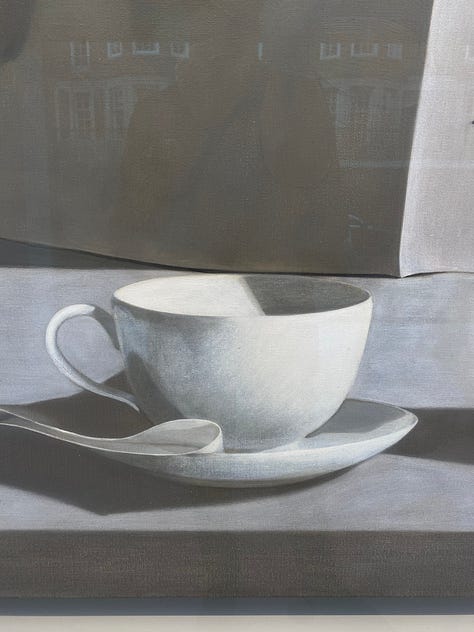

Only in the painting, It’s Coming From Inside The House (2024), is this made the most literal. The painting shows a scene of a bourgeois breakfast table, a woman (we presume by the manicured nails just visible) is obscured by a large blank newspaper, which she reads. Around her, on a white tablecloth rests a teacup and saucer with napkin, an elegant and darkly silver teapot. The scene is quotidian, mundane, tranquil, perfectly unblemished until one spots a Lynchian shadow figure – small, in the reflection of the teapot. This is maybe the most didactic of the paintings, and I do wonder if this dark ‘horror film’ figure in the teapot was a bit on the nose. When Weyant is at her best, these details, which conceptually “fold” the painting in on itself, don’t act so much as they suggest disruption: they are between silence and protest.

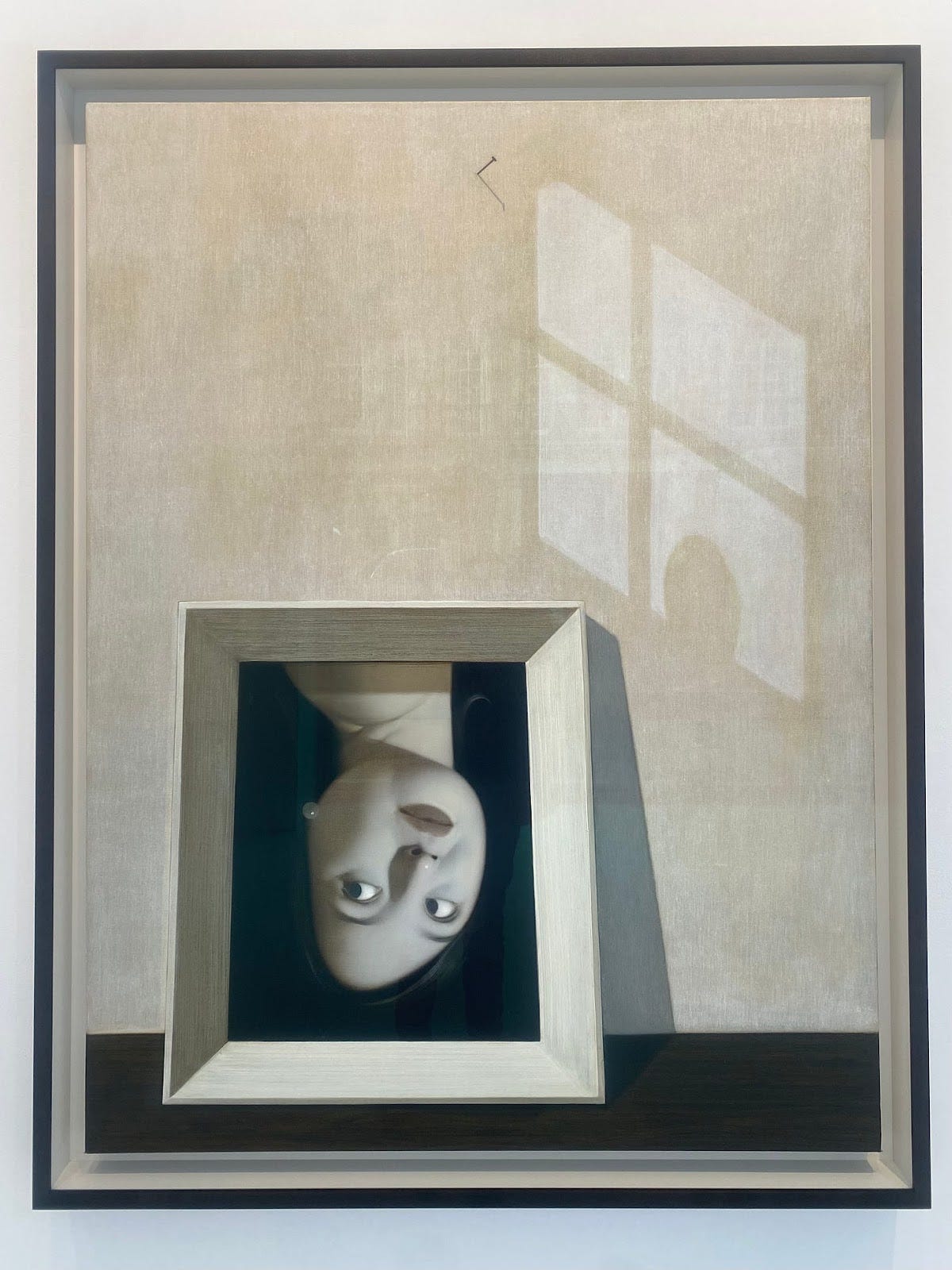

Another painting titled, Here, My Dear (2024) plays with the idea of a frames within frames. We are shown a blank beige-white wall. Against the wall leans an upside down painting - a framed Vermeer-style portrait of a porcelain cheeked woman. It leans at a slight angle against this wall waiting to be hung. We see a single nail is hammered into the beige wall presumably for this purpose. A black band at the bottom designates the floor, perhaps a dark carpet. Alighting on the empty wall askew, is the light from an ‘out-of-frame’ window.

There are a few movements of the eye that carry this painting first to the upside down portrait leaning on the wall, its excessive detail and naturalism, demands all our attention and admiration: the fact framed painting leans against the wall adds the additional virtuosity of having to render this warp in perspective, similar in theme to Parmigianino's Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (c. 1524). Our eye then moves to the blank expanse of the wall: the majority of this painting could be, we think to ourselves, a lack of a painting, a blank canvas. Only then do we find the nail, modest, pert, and asserted by a simple shadow. It seems subtly to designate the signifier “wall” to what otherwise could remain a primed canvas.

This semiotic play caused by the nail (which gives meaning in a similar sense as the shadow gives meaning to the ribbon) also alludes self reflexively, first to the unhung painting within a painting, then, in turn makes us aware of the “hungness”, that is to say, the presentation of the actual, real painting in the gallery in front of us: the present, the gift of the painting, so wrapped up, so theatrical and on display. I think this is also cleverly “doubled” in the presentation of the paintings by the fact that all these paintings are framed behind glass so that, with the light of the street behind me, my own reflection becomes part of the paintings allusive techniques. So much so that I ‘stop’ seeing the painted light on the beige wall, and experience the small round shadow as my own head!

And maybe because the nail is painted exactly where we can imagine a certain undisclosed nail on the other side of the frame, that which hangs the painting on the gallery wall, we experience a brief moment of semantic distortion. We are brought to a certain understanding that this is a picture of a nail piercing a painting rather than a bare wall with a nail and an unhung painting. What I am left with, is this strange sense of a nail rupturing the porcelain, skin-like patina of the painting and the violent associations of that destruction.

Weyant has become famous first as a remarkable painter and then as a celebrity in the art world. Her life, unlike most artists, is one of expensive characterless houses, smooth complexions, stilettos, dazzling white teeth, red carpets and moneyed individuals. It’s a privileged echelon and a heightened reality, a surreality, if you will. Exaggerated, and exact, there can’t be missteps in such a spotlit world of exteriors and appearances.

Weyant often depicts characters and objects as cartooned versions. She shows us a world emptied out of meaning and reality. A world of cartoon-girls, props, cardboard-flowers as though for the theatre or for some film set. It is not difficult to see the similarities between a cartoon world and a celebrity world. Both the celebrity and the cartoon are a reductive representation showing the features of its subject in an exaggerated manner. The cartoon shows, for example, a mouse. It is rid of details, a 2D simulacrum, by exaggerating the nose, the tail, the ears, the small body, no depth, shade, or psychology: it hides the complexities of the creature, the critter, the animal itself and gives us Mickey Mouse. Who is, literally, a ‘Looney toon’, a schizo mouse. The celebrity similarly shows a representation of someone real, a Taylor Swift or a Timothee Chalamet, we are all familiar with these figures, but only insofar as they are stripped of a certain human-quality and replaced by a god-like exaggerated exterior: mundane, bland, perfect.

Whether it’s the art world, celebrity, middle-class domesticity or an image of a pretty, blond girl what Weyant is interested in is schizophrenising this exterior, upsetting the status quo but not disrupting it: alluding to the reality of the thing, the shadow of the ribbon, but not pulling it apart. It isn’t to destroy the whole thing, but simply to point out that ‘this, this here is real.” That’s enough. Just enough to threaten the entire picture. Just one rogue, lunatic signifier that doesn’t quite add up.